Stuart Lester was the recipient of an unwritten letter of gratitude I had been carrying in my thoughts. Today was Stuart’s funeral. I can’t give him that letter any more. So the following is my way of writing that letter. And, as most letters of gratitude are, it is (uncomfortably) as much a letter about Stuart as it is a letter about me.

Stuart was a lecturer at the University of Gloucestershire, in a small but growing graduate program in Play and Playwork. I joined the program in 2012, after half-jokingly googling “Masters in Play,” thinking that there was no way that such a program existed. When I found that it did, I was soon on a plane from Boston to London, and then on a train to Gloucester, and then standing in a classroom with Stuart, who had asked me and my fellow graduate students to find a way to get from one door to another without ever touching the floor.

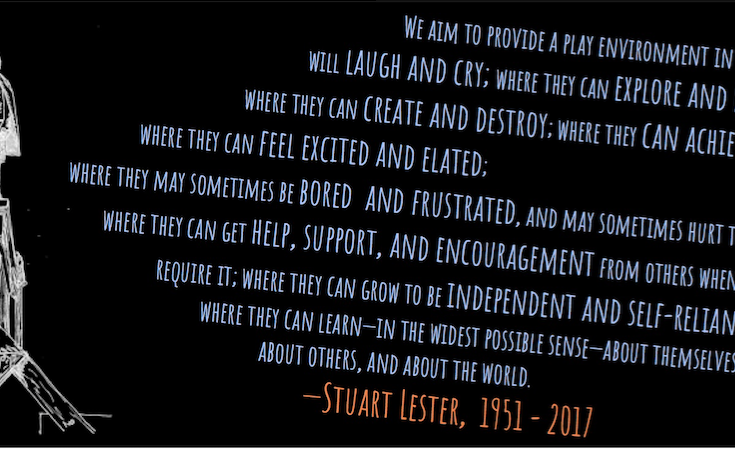

Serendipitously finding this graduate program was like going to Hogwarts. It was as if I found out that I wasn’t a weirdo: I WAS A WIZARD. Or, perhaps, a playworker. Here was a program that artfully drew from so many disciplines: evolutionary psychology, sociology, geography, and even critical theory. In their sampling of wide swaths of academic literature and life experience, Stuart, and his co-lecturer Wendy Russell, approached the study of play as they might approach a study of love: understanding that, as Gordon Sturrock writes, play is something “too big” to define. In this program, play was investigated in a beautiful, wholehearted and generous way: playfully.

In the following years of my participation in the program, I never met Stuart again in person. He existed in my life as a kind and disembodied voice on my computer who would often start a lecture by describing the weather at his home in Manchester. Stuart would then take his students on a wild journey through theory and practice that felt somehow punk in approach. Stuart elegantly crossed disciplinary lines like a kid vaulting a barbed fence separating him from something wonderful and exciting. It seemed that he approached research from a ludic state: an optimism about what more can be done.

In his writing and discussions, Stuart often spoke of non-representational theory, which focuses on the embodied moment: how stuff and bodies collide in time and space. My interactions with Stuart were, after that first meeting, never face to face but were still fully embodied in the collision of the moment: Stuart + computer + me + cats clambering onto the keyboard + fellow students + ideas + ideas + ideas.

In the weeks following Stuart’s death, I have been re-listening to those lectures, and it has reminded me of the degree to which Stuart radically shifted how I thought about play, space and children. In one lecture, Stuart addressed this shift.

“I would say that playing is a desire to see what more can be done,” Stuart said. “But it’s largely preconscious. It’s not a rational thought. It is a way of bodies moving restlessly with each other and with the materials in their environment.

“Now that’s quite a big shift in thinking that we have to make to get to that point. But having got to that point, it may change your perception of things.

“It may change the way that you start to look at children’s play. And we start to become not so much focused on the type of play, or classifying it as ‘is this play, is it not play’ but more about looking at the ways that bodies, materials, symbols, histories and so on combine to produce that particular moment.”

In another lecture, Stuart continues this train of thought, talking about how any particular moment as a collection of bodies, each body bringing its history and own trajectory into that moment.

“They all have a future time, a way of moving forward and going on,” Stuart said. “Bodies are in a continuous state of going on.”

It is strange listening to Stuart’s voice knowing that his voice is no longer “embodied” somewhere, in a literal sense. But this idea of bodies going on, spoken in Stuart’s own voice, recalibrates me as I feel sad that Stuart is no longer living. It reminds me of Aaron Freeman’s “eulogy from a physicist.” Freeman says that it could be some comfort to the bereaved that, actually, the energy represented by our bodily form does not disappear:

“According to the law of the conservation of energy, not a bit of you is gone,” Freeman writes. “You’re just less orderly.”

Less orderly: now that’s something Stuart– a rule breaker, and a bit of a quantum physics geek– would have liked. Stuart was a brilliant and rigorous academic, and was brilliant in part because he knew the rules and when to break them. He could talk about poop and critical theory in the same sentence. He could shoot the shit without a trace of bullshit, and talk about children’s play in a way that never lost sight of the child. I’m not sure what Stuart would have thought about this metaphor, but I think he wrote and taught as a playworker: as if he writing from a perch near the play of children, very very present, writing with authority but without being authoritative.

I owe Stuart a great debt because Stuart was my playworker. He was kind; he was present; he was respectful. His tutoring changed my perception of things. As we and my fellow students discussed children and play in so many course modules, it felt that he was not teacher and I student but rather we were teacher-students and student-teachers, journeying together. He was humble and optimistic that each day would bring something new to learn.

I’m not sure Stuart knew this, but it is in large part due to Stuart’s unsettling effect on me that I moved across the country to a new job in a new place. Still in the long distance graduate program, I began working at The New Children’s Museum with a group of coworkers who staffed exhibition spaces. Over the course of several years, under Wendy and Stuart’s mentorship, I began introducing playwork to the practice of this group. Stuart and Wendy had been my playworkers, and now I could be playworker to this group: playfully figuring out whether this practice could take hold in a children’s museum. Today, eight “Museum Playworkers” work in New Children’s Museum spaces, gathering each day for reflection and sharing. We are student-teachers and teacher-students, learning from each other and our space. We are in a continuous state of going-on.

Just a week before Stuart died, more than five years after I first made that trip to England, a few colleagues and I facilitated a session called “Playworking the Children’s Museum” at the Association of Children’s Museums conference. People from children’s museums all over the world approached us after the session, eager to learn more. Stuart and Wendy gave me a gift: this thing called playwork. It is a gift that gets bigger the more you give it. Thousands and thousands of miles from Manchester, there are now playworkers who, perhaps, might give children (and each other) the love, respect, and presence that Stuart gave me and all his students.

Writing this today, far away from Stuart’s funeral, is complicated. I wish I could have told Stuart all of this, instead of holding on to this debt of gratitude, allowing it to collect interest while I tried to adequately express it. Letters of gratitude are, after all, love letters: love for the person we wish to thank, and love for the person we have become.

I find some comfort in thinking that the letter I write to Stuart now is not so different than the letter I would have written to him weeks ago, before I learned of his passing. So much has changed, and yet so little has changed. His ideas are still here. His way of seeing the best in people is not gone. His words– recorded and punctuated by encouragement– still challenge us to think differently and to reframe long-held assumptions about children and play and space. I am not gone, nor is Iyari or Catherine or Jesse or Hannah or Jill or Amber or Diana or Suzie or Leah or Jaclyn or any of the children these playworkers work with everyday at the museum. All of that energy is still here.

Stuart is still here. He is just less orderly. And I think Stuart would be comfortable with that.

I think you have done exactly what you should have done in that you have made me, and possibly others, to stop, read, think and respect the world of play, human interaction and the role of learning and respect. Bravo I’m sure his less orderly self would be delighted.

Thank you, Sally!

Wonderfully stated, this totally resonates with my own thoughts & feelings about this very special man.

He was one of a kind.

That is beautiful Megan, and so right. I have shared many similar thoughts since hearing of Stuart’s death. Well put!

Megan, you have summed up in one letter the wonderful, humorous, kind and gentle person Stuart was. His legacy will go on through all the playworkers he had contact with, thier contact with other playworkers and of course, through the lovely Wendy. Yes, he had a habit of turning our thoughts of play upside down but for all the right reasons. Now, when I observe children playing, I always think “what if” and I wonder now “what if Stuart was here”? Sadly missed but happy memories for all who had the privilege to know him.

Thank you!

I know that man, I will continue to be inspired by him “as if” I could have lunch with him!